Twitch divination, also known as palmomancy (from Greek παλμός, “quivering motion”), is one of many sub-genres of physiognomy, that is, divination which is based on the observation of the human body. It is based on the assumption that the involuntary twitches of different limbs of a person’s body are a sign, either foretelling future events in that person’s life, or revealing secrets otherwise unknown to him or her. It is a very ancient form of divination, which goes back to Mesopotamian texts of the second millennium BCE, and it has enjoyed a great popularity in many different languages, including Greek, Syriac and Hebrew. And it was – and still is – very popular in the Arab world, as any Google search for the verb اختلج, or the noun اختلاج immediately reveals.

Like many manuals of divination, manuals of palmomancy have a very simple structure, consisting of a long string of sentences which have two basic parts – “If (a certain limb twitches) it signifies (that this and that would happen, or has already happened).” And like many other manuals of physiognomy and medicine, manuals of palmomancy are usually arranged from head to toe. However, there is a great deal of variation between the different manuals, since some texts focus only on the major limbs of the human body, while others cover each tiny organ that might twitch. And some texts add another element to the divinatory process by considering the gender and social status of the person whose limb twitched, as in “If a limb X twitches, for a slave it signifies A, for a virgin woman it signifies B, for a widow it signifies C,” and so on. And as there was no overarching logic governing the relation between the limb and the significance assigned to its twitching, the relations between signifier and signified were in constant flux. These factors, and the fact that manuals of palmomancy circulated in many different languages, resulted in a bewildering array of palmomantic texts, all of which look quite similar, but differ from each other in their specific details. This was not lost on the editors and copyists of these texts, who often listed more than one meaning for each twitch, supplementing the main entry by additional entries attributed to other sources, as in “If a limb X twitches it signifies A, but the Persians say it signifies B, and the Indians say it signifies C.” And as with almost all modes of divination, the more complex the texts became, the more room was left for their expert owners to decide which signification to choose in each specific case.

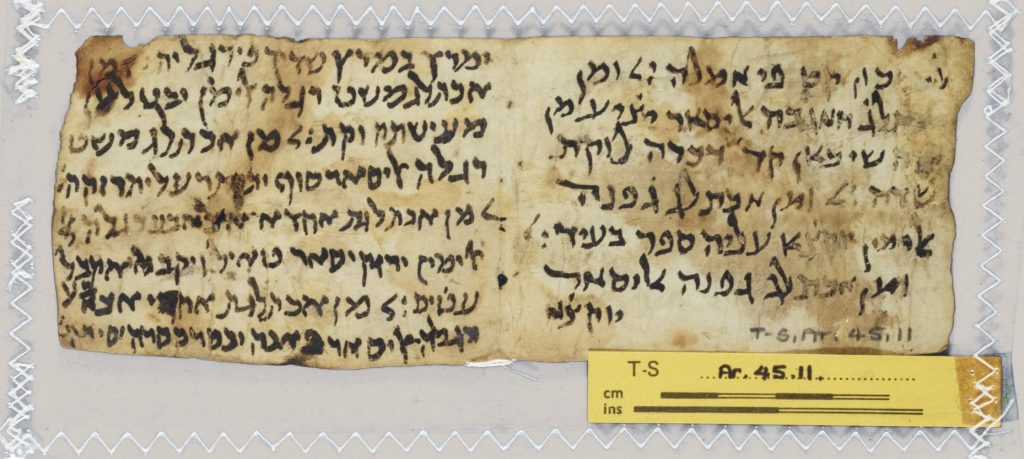

In the Cairo Genizah, the repository of Jewish texts which was in use from the 11th to the 19th century, there are more than a dozen fragments of twitch-divination manuals, in three different languages. The oldest text is that written in Aramaic, which was the Jews’ main language prior to the Muslim conquests of the 7th century. This text has yet to be published (and I plan to do so in the near future), but a Hebrew version thereof enjoyed a wide circulation in the Middle Ages, was printed several times, and is still available in some bookshops in Israel. In the Cairo Genizah, there are no fragments of this Hebrew text, but another Hebrew palmomantic text, written in a Spanish hand of the fifteenth century and displaying many Spanish or Ladino loanwords, is found in Oxford, Bodleian Heb. f. 106.60-61. But the largest number of Genizah palmomantic fragments is in Judaeo-Arabic (both in the earlier, phonetic, form of writing Arabic in Hebrew letters and in the “standard” system of transliterating Arabic in Hebrew letters) and in Arabic written in the Arabic script.[1] Of these texts, the best preserved is a book of twitches attributed to Shem, son of Noah, which is extant in two different copies. The first copy, preserved in T-S A45.21, consists of a single paper folio, paleographically dateable to around the twelfth century, that preserves the beginning of the text and the sections from the eyes to the upper lip.[2] The second copy, which I pieced together from four different fragments in Oxford (Bodleian Heb. g 8.52–53) and Cambridge (T-S Ar. 45.11; T-S AS 157.179; T-S AS 173.423), covers the sections from the eyes to the lower lip, and then, after a long lacuna, from the thighs to the toes, as well as the ending of the entire manual. At the colophon the scribe who wrote this manuscript, or a part thereof, identified himself as “Menashe birabbi Isaac the cantor, may he rest in peace,” who is known from other Genizah documents of the mid-twelfth century. This second copy also is interesting for its physical features, as it is a “pocket book” parchment codex, whose pages measure ca. 8 cm (width) by 5 cm (height) (see figure 1). This format no doubt made the booklet very easy to carry around on Menashe’s travels, where he might observe people whose limbs twitched, or feel his own limbs twitching, and would thus know what lies ahead for others and for himself.

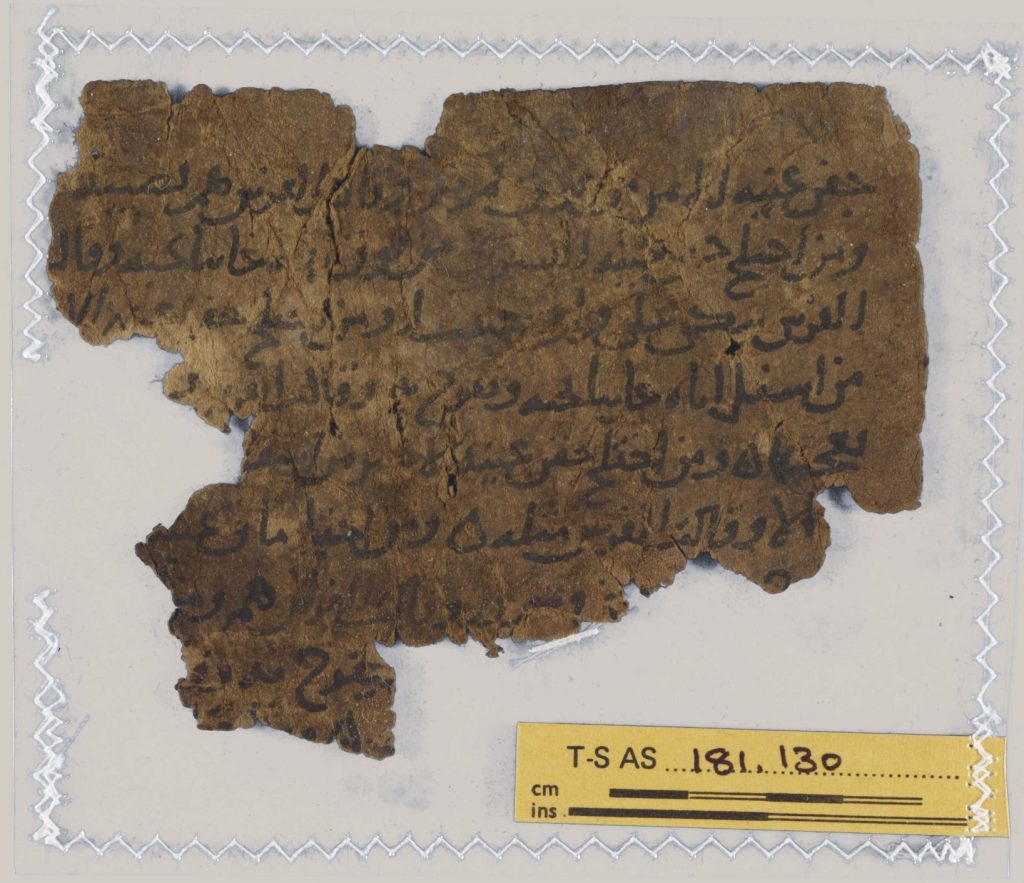

So what should you expect if, for example, your eyelid twitched? Well, that depends on which text you choose to consult. If you read the text attributed to Shem, son of Noah, you will learn that “If someone’s right eyelid twitches, a long journey will be destined for him; and if his left eyelid twitches, a short journey will be destined for him.” But if you consult another palmomantic fragment from the Cairo Genizah (T-S A.S. 181.130), which is written in the Arabic script (see figure 2), you will learn that things are not so simple. First, there is a different significance not only for each eye, but also for the upper and the lower eyelid. Second, for each limb this text provides a significance, followed by an alternative interpretation, attributed to the Persians. For example, “if the upper eyelid of one’s right eye twitches, (it means that) he will become ill, and the Persians say that he will encounter sorrow.” However, “if the lower eyelid of one’s right eye twitches, (it means that) an absent person whom he loves will come to him, and he will rejoice in him, and the Persians say that he will be amazed by (there is a lacuna in the text here).” If my own eye twitched, I would probably opt for the most optimistic scenario, and conclude that I will go on a journey and meet a friend whom I have not seen for a long time. But who knows? maybe I would go on a journey, become ill, and encounter sorrow? Apparently, what you read is what you get, and all foretold in a blink of the eye.

Professor Gideon Bohak holds the Jacob M. Alkow Chair for the History of the Jews in the Ancient World at Tel Aviv University, where he teaches at the Department of Jewish Philosophy and Talmud. His main field of research is the history of Jewish magic. His most recent books include A Fifteenth-Century Manuscript of Jewish Magic, Los Angeles, 2014 (in Hebrew), Magie, anges et démons dans la tradition juive, Paris, 2015 (with Anne Hélène Hoog), and Thābit ibn Qurra On Talismans and Pseudo-Ptolemy On Images 1-9, Florence, 2021 (with Charles Burnett). His many articles are devoted to the publication and analysis of new texts, and to programmatic discussions of Jewish magic and Jewish history.

[1] The fragment that is written in Early Judaeo-Arabic in the Phonetic Spelling will be published shortly in Joshua Blau z”l and Simon Hopkins (with contributions by Gideon Bohak), Early Judaeo-Arabic in Phonetic Spelling: Texts from the End of the First Millennium, vol. 2, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi, 2023 (in Hebrew).

[2] The first copy was published by Simon Hopkins, A Miscellany of Literary Pieces from the Cambridge Genizah Collections: A Catalogue and Selection of Texts in the Taylor-Schechter Collection, Old Series, Box A45, [Genizah Series 3], Cambridge: Cambridge University Library, 1978, pp. 67-71.