1. Chapter 49 from the Book of Genesis contains the so-called Blessing of Jacob, a compilation of sayings, which are framed as Jabob’s deathbed address to his twelve sons, each of them representing one of the tribes of Israel. Raising thus questions of identity and cultural delineation, Jacob’s Blessing often became the starting point for polemics between Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Samaritans.[4]

2. Since antiquity, the Jewish reception of the verses on Judah displays a marked eschatological tendency, typically reading the enigmatic Hebrew term Shilo (שִׁילֹה) as a reference to the Messiah. Christian theologians incorporated this understanding into their christological exegesis, polemicizing against Jewish messianic concepts. Samaritan exegesis, however, which emphasizes the primacy of Joseph – in contrast to the Jewish-Christian focus on Judah – commonly identifies Shilo with Solomon.[2]

The Samaritan understanding of the verses on Judah

3. The verses on Judah in the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) differ substantially from the Jewish Masoretic text (MT) and express a negative assessment of Judah. Genesis 49:10–12 is particularly illustrative in this regard (differences to MT marked bold):

לא יסור שבט מיהודה ומחקק מבין דגליו[3] עד כי יבוא שלה ולו יקהתו [4] עמים אסורי לגפן עירו ולשריקה בני איתנו כבס ביין לבושו ובדם ענבים כסותו חכלילו[5] עינים מיין ולבן שנים מחלב[6]

Based on the Samaritan Targumim, the verses can be translated as follows: “The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from among his hosts, until Shilo comes. To him the people are gathering. He turned aside to his city, Gaphna [i.e., Jerusalem], and the sons of his strength to emptiness.[7] He washes his garment in wine and his robe in the blood of grapes. His eyes are turbid from wine and white are his teeth from fat.”[8]

4. A similar rendering of the first part of verse 11 (“He turned aside to his city, Gaphna, and the sons of his strength to emptiness”) as a pejorative reference to Jerusalem[9] is reflected in the Arabic column of the triglot Ms. London, BL, Or 7562, which is probably the earliest version of the Samaritan Arabic translation of the Pentateuch.[10] However, none of the manuscripts used in Shehadeh’s edition of the Arabic translations of SP attest to this understanding. For example, Ms. B of Shehadeh’s edition reads:

| “The reign shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from among his hosts until Solomon comes. And the peoples will follow him. He binds his ass to the vine and his ass’s colt to the choice vine (?).[11] He washes his clothes in wine and his garment in grape juice. The eyes are crooked from wine and the teeth are white from fat.” | لا يزول المُلك من يهوذة والمرسّم من بين بنوده حتى يأتي سليمان واليه تنقاد الشعوب يربط في الجفن عيره وفي السَّيروقة بني أتانته يغسل بالخمر لباسه وبعصير العنب كسوته مُزَوَّر العينين من الخمر وأبيض الأسنا ن من الشحم[12] |

This translation expands the negative assessment of Judah by identifying Shilo with Solomon, while its polemical stance is centered around the consumption of wine and meat as a sign of Solomon’s debauched behavior and lack of self-control.

Excerpt from the Samaritan-Arabic commentary Šarḥ al-barakatayn

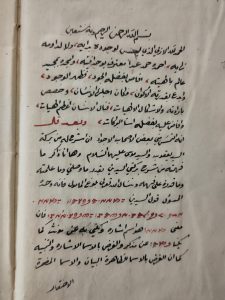

5. The context of this understanding is further illuminated in the Samaritan-Arabic commentary Šarḥ al-barakatayn (“The Explanation of the Two Blessings”), commonly ascribed to the prolific Samaritan polymath Ṣadaqa b. Munaǧǧā (died after 1223). However, it is more likely that it was composed by an unknown author at a later date, as a comparison of the text with Ṣadaqa’s writings indicates.[13] Nonetheless, the composition is an important witness for medieval Samaritan Arabic exegetical traditions, containing a commentary on Genesis 49 (“Jacob’s Blessing”) and Deuteronomy 33 (Moses’ Blessing). The following excerpt is an abridged version of the commentary on Genesis 49:10–12, transcribed from its oldest textual witness, Ms. Manchester, John Rylands Library, 228, fols. 58r–60r:[14]

| “It (the text of the Torah) says: The reign shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from among his hosts until Shilo comes. (Gen 49:10) […] And its meaning is, that Judah’s children and his offspring remain as long under God’s blessing and the (pious) obedience to his law[15] until the one mentioned before (i.e., Shilo) comes. He removes the law, adopts a vile belief and permits negligence in religion, so that the fool may follow him. And there is little respect for religion, while those (who follow Shilo) are the majority. Because of that, it says: And the peoples will follow him. (Gen 49,10) This means, that many people will follow him, because those who act righteously are small in number. […] And this (i.e., Shilo) is Solomon because the smallest of sins he committed, was that he took from the daughters of the kings dissenting from religion and married them, and (he committed even) more of the major sins. […] It says: He binds his ass to the vine and his ass’s colt to the vine’s branch.[16] (Gen 49:11) This refers to his (Solomon’s) propensity towards the excessive planting of vine trees (and) his love for pressing wine. But too much wine distracts the mind and hinders the body to rise, just as the clouds hinder the sunlight to rise as they are blocking it.[17] And in its saying: And his ass’s colt to the vine’s branch (ibid.) he is described by way of leisure, sensual worldly delight, and the love for distracting wine. This, however, is contrary to what is required by the (pious) obedience to God, in pursuit and fulfillment of the duty of religion and the precepts of the acts of devotion. […] It says: His eyes are crooked from wine. (Gen 49:12) Here, the effect of the covetous power is being described when it triumphs [over the mind]. This can be concluded from its (the power’s) traces, which is that the eyes are squinting from the [effect of the] wine, because he (Solomon) was irrepressibly greedy and full of it. [It says]: And his teeth are white from fat. (ibid.) (This is) because he consumed large amounts of meat. But the latter’s consumption is surely dispraised by law and by tradition.” | قال לא יסור שבט מיהודה ומחוקק מבין דגליו […] ومعناه ان اولاد יהודה وذراريه لم يزالو تحت بركة الله وطاعة شريعته الى ان يجي المذكور فينزع الحق ويتخذ مذهباً ردياً ويرخص في الدين ليتبعه الجاهل وقليل الاحتفال بالديانة وهم الاكثر ولهذا قال ולו יקהתו עמים […] وذلك هو סלימאן لانه اقل ما فعل من العصيان انه اخذ من بنات الملوك الخارجين عن الدين فتزوج بهن واكثر من عمل الكباير […] قال אסורי לגפן עירו ולשרקה בני איתנו وهو ميله الى الاكثار من نصب الكروم محبة في اعصار الخمور والخمر يزيل العقل ويمنع اشراقه على البدن اذا اكثر منه كما يمنع السحاب اشراق ضو الشمس على ما يسامتها وفي قوله ולשרקה בני איתנו وصف له بالراحة ولذة الدنيا وحب المدام الملهى والشاغل وهذا بضد ما يجب في طاعة الله من النهوض والقيام بواجب الدين وفرايض العبادات […] قال הכלילו[18] עינים מיין وصف هاهنا فعل القوة الشهوانية اذا غلبت فاستدل عليها من اثارها وهو ارود[19] العينين من الخمر لكثرة شرهه وامتلاه منه ולבן שנים מחלב من كثرة تناوله اللحوم وقد ذم استعمالهما شرعاً ونقلاً |

Commentary

6. Proceeding from the identification of Shilo (Gen 49:10) with Solomon, the commentary focuses on the lack of Solomon’s moral qualities, as the author refers to his excessive consumption of wine and meat, and the negative character traits associated with it. The understanding that Gen 49:11‒12 refers to Solomon is also prevalent in one of the Samaritan chronicles, the so-called Chronicle II edited by Macdonald. Manuscript H 2, written in Neo-Samaritan Hebrew, consistently uses Shilo instead of Solomon.[20] Commenting on the verses on Judah, it reads: “Thus applies the statement of our ancestor Jacob concerning the tribe of Judah to the times of King Solomon the son of David. […] All these words apply in the same way to the deeds of King Solomon the son of David, for he behaved exactly as this statement said.”[21] Similar to Šarḥ al-barakatayn, this Samaritan interpretation not only opposes the Jewish identification of Shilo with the Messiah, but also criticizes Solomon’s sinful behavior.

7. In this regard, the author of Šarḥ al-barakatayn mentions also Solomon’s controversial predilection for foreign wives. Ultimately going back to 1 Kings 11:1–14, this tradition is obviously not originally Samaritan (the biblical books beyond the Torah are not part of the Samaritan canon).[22] However, it entered the Samaritan tradition in the Middle ages, most probably through Arabic sources, and it is also prevalent in the Samaritan chronicles.[23] The main reason behind Solomon’s negative portrayal in the Samaritan tradition lies in his role as the builder of the Jerusalem Temple, the schismatic sanctuary of the Jews, according to the Samaritans.[24] The negative account of Solomon in Šarḥ al-barakatayn thus aims to disqualify the Jewish temple, the Davidic line, and the tribe of Judah as a whole, in gross opposition to the priority that is given to them in Jewish and Christian exegesis.

8. In spite of these discrepancies in the general contextualization of the verses on Judah, there are also occasional points of contact and cultural exchange between Samaritan and Jewish traditions, as already seen in relation to the tradition of Solomon’s problematic character. Another example is the motive of Judah’s drunkenness, which was also discussed among Karaite exegetes. Much like the Samaritan-Arabic translation, the prolific Yefet ben Eli (10th century) translates verse 12 without reproducing the elative in Arabic: אזוראר אלעינין מן אלכמר (approximately: “The eyes are crooked from wine”).[25] And he explicates: ודלך אן אזוראר אלעין ידל עלי אפראט אלסכר (“and this is because ‘the crookedness of the eye’ points to the exaggerate state of being drunk”).[26] Similarly, Sahl ben Maṣliaḥ (second half of the 10th century) states in his commentary to Genesis: והו זוראן אלעינין יכון מן כתרה אליין (“and this means ‘crookedness of the eyes’, which stems from the abundance of wine”).[27] However, this understanding is assessed positively since the verse points to the richness of the land, according to Sahl, or to favors granted by God, according to Yefet.[28] Thus, while Karaite exegetes understand Judah’s drunkenness as an allegorical expression of abundance, the author of Šarḥ al-barakatayn reminds the reader of the consequences of alcohol consumption and cautions: too much wine distracts the mind!

Acknowledgements: The article is based on research carried out for my doctoral dissertation at Martin-Luther-Universität Halle–Wittenberg. I would like to thank Merlin Reichel for copy-editing this text.

Jasper Bernhofer is a PhD candidate in Judaic Studies at Martin-Luther-Universität, Halle-Wittenberg. He obtained an MA in Semitic Studies at Freie Universität Berlin and studied abroad at INALCO in Paris and at Tel Aviv University. Among his research interests are the Samaritan Pentateuch, biblical exegesis and philosophy in the medieval Islamicate world, manuscript studies, and digital editions. In his thesis he provides a critical edition, translation, and commentary of the medieval Samaritan Arabic commentary šarḥ al-barakatayn on Genesis 49 and Deuteronomy 33 and examines its significance for shaping religious identity by comparing it with Karaite, Rabbanite, and Christian commentaries.

Suggested Citation: Jasper Bernhofer, “Solomon’s Sin: Medieval Samaritan-Arabic Exegesis of the Verses of Jacob’s Blessing (Genesis 49:8–12)”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 19 December 2023, URL: https://www.jewisharabiccultures.fak12.uni-muenchen.de/biblia-arabica-blog-solomons-sins-medieval-samaritan-arabic-exegesis-of-the-verses-of-jacobs-blessing-genesis-498-12/

References