The Arabic Bible has served various functions throughout its history. In the 19th century, for example, it was an important literary medium of the Christian Nahda as well as an object of scientific curiosity for European orientalists.1 The following is about a publication that brought both functions together. In this way, unwittingly, this publication has also become a document for the looting of one of the most important archives of historical Arabic Bible translations and Christian Arabic manuscripts more generally. I would like to show here how excerpts from a supposed Arabic translation of the Bible turn out to be traces of a lost manuscript of this archive.

2. In March 1894, the Cairo-based jorunal al-Muqtaṭaf, an encyclopaedic periodical of the Christian Nahda propagating literary and scientific progress, published an anonymous article entitled “Treasures of the Sinai or the Arabic Books on Mount Sinai”.2 The contents of this four-page contribution were rapidly reproduced in a number of newspapers and academic journals around the globe.3 They were found to be either quite sensational or quite sensationalistic. The article’s starring piece is, despite the title, not an Arabic manuscript, but a manuscript of the Gospels in Christian Palestinian Aramaic, a western variety of Aramaic, which was only beginning to be properly studied at the time.4 The article’s editors highlight that the text sample (Mark 9:11–12) is written “in a language similar to the form of Aramaic, which was in common use in Syria in the time of Christ”.5 But not only did the language – supposedly – carry one back to Jesus’s lifetime, its material support, the manuscript itself, was believed to be perhaps the most ancient copy of the Gospels, i.e. the closest in time to when the Gospels were written. Even though the other manuscripts mentioned in the article were centuries younger and in Arabic, the Christian Aramaic Gospels and the site of their find, St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, could not fail to create a captivating aura of antiquity.

3. The Gospels manuscript is one of a total of eight manuscripts that are described in more detail. The readers are told that their discoverer was a certain German named Dr Grote who photographed more than twice this number of manuscripts in the library of St Catherine’s Monastery. This German discoverer is the collector Friedrich Heinrich Ludwig Grote (1861–1922).6 Today we know that Grote was responsible for the dislocation and dismemberment of hundreds of fragments and whole codices from Sinai. Hence, it comes as no surprise that none of the eight manuscripts mentioned in al-Muqtaṭaf appears to have stayed in the library of St Catherine’s Monastery. I was able to identify the provenance history and present location of seven of them. They are now housed in five different European public and private collections. I write about these manuscripts in a forthcoming publication.7 Here, I would like to detail how I went about tracking one of them by means of an Arabic Bible quotation.

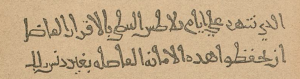

4. This manuscript – or fragment of a manuscript – is described in most scanty terms in the 1894 article. The editors introduce it as “a leaf (ṣaḥīfa) on which are verses taken from (muqtabasa min) the sixth chapter of the First Letter to Timothy”.8 Fortunately, the article also offers a wood cut facsimile (figure 1), sampling two lines, as well as a transcription of four lines of text. This, first of all, allows us to more narrowly determine the quoted passage as 1 Timothy 6:13–14. On this basis, two lines of investigation suggest themselves, one palaeographical and one text-critical. As we will see, it all bears on what is meant by “taken from” (muqtabasa min). If this means that the quoted verses “derive from” an Arabic translation of 1 Timothy, we are probably dealing with a Bible manuscript, whereas if it means that they are only “quoted from” 1 Timothy, the manuscript that was reproduced in al-Muqtaṭaf might not be a Bible manuscript at all. It could be any sort of theological text or commentary.

5. The palaeographical sample offers some clues as to the possible date of the manuscript. The script is an example of the category of Christian Arabic New Style script, according to the classification of Miriam L. Hjälm in a recent study of early Christian Arabic scripts.9 This script is characterised by its vertical extension (for instance the letter ṭāʾ clearly exhibits more vertical than horizontal extension, as can be seen in figure 1). It typically features in manuscripts from the late 9th or the 10th century CE. This already gives us an approximate time frame. Given that the editors of the 1894 article highlight in another case that the writing support is parchment, the manuscript in question may consist of paper. This would support a 10th-century CE date.

6. Next, we can look at the four lines of transcribed text (together with my translation):10

| (1) | I implore you before God, the giver of life to all, and before Jesus Christ, | اوصيك بين يدي الله محيي الكل وبين يدي يسوع المسيح |

| (2) | who testified the good confession in the days of Pontius Pilate, | الذي شهد على ايام بلاطس البنطي بالاقرار الفاضل |

| (3) | that they preserve this good faith without stain | ان يحفظوا هذه الامانة الفاضلة بغير دنس الى |

| (4) | until the time of the appearing of our Lord Jesus Christ. | وقت ظهور ربنا يسوع المسيح |

Thanks to the work of Vevian Zaki, we are now very well informed about the different Arabic versions of the Pauline Epistles.11 I made a test comparison juxtaposing the text sample with three Greek-based and two Syriac-based versions. This comparison showed that it exhibits the highest lexical agreement with two Greek-based versions, which Zaki groups as ArabGr3 ( approx. 87.4% agreement) and ArabGr1 (approx. 83.6% agreement). The comparison, however, also showed that there is no complete agreement with any of the known versions.

7. I would like to highlight two particularly odd features. The first is the form of the verb ḥafiẓa (“to preserve”) in line 3. The sample has it in the third person plural masculine (subjunctive mood): yaḥfaẓū. First of all, we should note that this word is not pointed in the facsimile, which means that it could also be read as second person plural masculine: taḥfaẓū. Still, either form creates problems with respect to the second person singular masculine suffix –ka appended to the verb uwaṣṣī (line 1), which stands at the beginning of this clause and on which depends the particle an (line 3), which introduces a subordinate clause starting with yaḥfaẓū/taḥfaẓū. By contrast, all known Arabic versions of this passage have the form taḥfaẓa (second person singular masculine).

8. The second oddity is the expression al-amāna al-fāḍila, “the good faith”, which occurs in line 2. For one, amāna is a strange translation for the original Greek entolē, “commandment”. Most versions render the Greek word as waṣiyya (for comparison, translations in Coptic (Bohairic) tend to borrow the same Greek word, while the Latin Vulgate has mandatum and the Syriac Peshitta has pūqdānā, which both mean “commandment”). What is more, in the Greek, entolē is followed by two negative attributes, aspilon anepilēmpton, “without stain (and) without reproach”. Morphologically, both are formed by means of a prefixed alpha privativum. All known Arabic versions of this verse emulate this construction by using two subsequent negated expressions (mostly bi-ġayr … wa-ġayr … or bi-lā … wa-lā). There is no known version that turns the first negative attribute into a positive one as in our text sample.

9. These two examples indicate that the text sample might reproduce a version that exhibits great proximity to Greek-based versions, but also has some peculiarities of its own. At this point, one could be led to conclude that the manuscript mentioned in al-Muqtaṭaf is an early witness to a possibly hitherto unknown Greek-based version (or recension of a Greek-based version) of the Arabic Pauline Epistles, which was very likely produced in the tenth century CE.

10. Yet, there still remains the possibility that the manuscript is not a witness to 1 Timothy at all. Hence, we should look for a text attested in early Christian Arabic literature that quotes 1 Timothy 6:13–14 in full. Even though this could in principle also be an original composition, I first looked for translations of Greek patristic texts. One text that fits the bill is Cyril of Jerusalem’s (d. 386 CE) Catechetical Homilies. The two verses are quoted at the end of Homily 5.

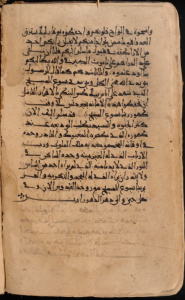

11. An early Arabic translation of this popular text is attested in MS Sinai, St Catherine’s Monastery, Ar. 309 (Sin Ar. 309, figure 2). The manuscript was produced by the scribe David of Ascalon (Dawīd al-ʿAsqalānī) in Jerusalem in 924/5.12 Paratextual features indicate that it reached St Catherine’s Monastery in the late 10th or early 11th century CE.13 In this manuscript, Cyril’s Homilies (Mawʿiẓāt) are found on ff. 1r–217r. Homily 5 occupies ff. 29r–33v. The biblical quote is found at the end of this homily and here we see that Sin. Ar. 309 reproduces almost the exact same text that was printed in al-Muqtaṭaf (textual disagreements are highlighted in red):

| al-Muqtaṭaf | Sin. Ar. 309, f. 33v:5–9 |

| اوصيك بين يدي الله محيي الكل وبين يدي يسوع المسيح الذي شهد على ايام بلاطس البنطي بالاقرار الفاضل ان يحفظوا هذه الامانة الفاصلة بغير دنس الى وقت ظهور ربنا يسوع المسيح | انا اناشدكم كما قال الرسول بين يدي الله محيي الكل وبين يدي يسوع المسيح الذي شهد على ايام بيلاطس البنطي بالاقرار الفاضل ان تحفظوا هذه الامانة <…> بغير دنس الى وقت ظهور ربنا يسوع الميسح |

12. Disagreements between the two samples are minimal. We can ignore the additional text kamā qāla ar-rasūl, “as the apostle said”. It may very well have been found in a part of the manuscript that was not reproduced in the 1894 article. The editors could well have chosen to omit it in order to give only the text of the biblical quote and they may even have wanted to give the impression that it comes from a Bible manuscript. However, if their manuscript was indeed an Arabic Pauline Epistles manuscript, they could easily have reproduced more than just the two verses. We can also ignore the difference in spelling of the name “Pilate”, i.e. Bylʾṭs instead of Blʾṭs. This is simply a matter of transcription and both variants are attested across Greek-based versions of this passage (by contrast, some of the Syriac-based versions have Fylʾṭws or Fylʾṭs mirroring the Syriac Pīlāṭōs, which is itself a transcription of the Greek).

13. The two important disagreements are in Sin. Ar. 309 the omission of al-fāḍila after al-amāna and the use of unāšidukum instead of uwaṣṣīka. The first is very likely a scribal mistake in this manuscript. The second is a proper variant and reflects a different approach in translating parangellō soi in 1 Timothy (the verb nāšada, “to implore”, is also used as the translation in Syriac-based versions) or rather, in translating diamarturomai, “beg earnestly of one”, which the text of Homily 5 has in this place. Since nāšada, like waṣṣā, is transitive it needs a direct object and, hence, picks up –kum in correspondence with taḥfaẓū. In fact, we now see that taḥfaẓū is the correct reading and that yaḥfaẓū in al-Muqtaṭaf is due to a false pointing of the first consonant.

14. What is more, Cyril’s text helps us explain the two oddities we noticed above. The Greek version of Homily 5 already disagrees with the biblical text: instead of tērēsai se tēn entolēn aspilon anepilēmpton (“that you [2nd pers. sg.] keep the commandment without stain [and] without reproach”) it reads tērēsai tautēn humas tēn paradedomenēn pistin aspilon (“that you [2nd pers. pl.] keep this faith which was handed down to you without stain”).14 Here, we find both an explanation for the form of ḥafiẓa, the use of amāna (translating pistis), and the fact that there is only one negative attribute.

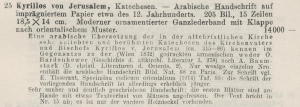

15. Without puzzling out all the philological details, the comparison clearly shows that the text sample in al-Muqtaṭaf very likely comes from an Arabic translation of Cyril’s Homily 5. Consulting Georg Graf’s Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, vol. 1, we find that “the oldest” witness to this Arabic version is found as no. 25 among a group of exiled Sinaitic manuscripts offered for sale in Katalog 500 of the Leipzig-based antiquarian, book seller, and publisher Karl Wilhelm Hiersemann (1854–1928).15 Scholars have previously identified manuscripts listed in Katalog 500 as coming from Grote’s collection. Graf himself pointed out that “a number of items from the collection first came into the possession of the antiquarian book store Karl W. Hiersemann in Leipzig”.16 As a matter of fact, at least one other manuscript mentioned in al-Muqtaṭaf, a Syriac-Arabic interlinear psalter, was offered by Hiersemann as no. 48 in Katalog 500. It is now kept in the British Library under the shelfmark Or. 16059 and is still uncatalogued.17

16. Unfortunately, we will probably never have a chance to compare the facsimile of al-Muqtaṭaf to olim Hiersemann 500/25. At some point in the 1920s or 1930s, it was bought by the Catholic University in Leuven.18 In May 1940, during WWII, the University Library was set on fire by German troops leading to the destruction of its entire manuscript collection including cataloguing material.19 All that seems to have remained of this manuscript, then, is the facsimile and transcription in al-Muqtaṭaf as well as the brief description (figure 3) in Katalog 500, authored by Anton Baumstark (1872–1948).

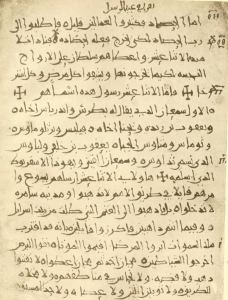

17. Based on Baumstark’s description, Hiersemann 500/25 was a 6th-/12th-century paper manuscript covering the first fifteen of Cyril’s 18 Homilies.20 Only the front board of the original binding was extant. It is not unlikely that Hiersemann 500/25 was originally quite similar to Sin. Ar. 309, containing both the Catechetical Homilies as well as Mystagogic Catecheses, which are often attributed to Cyril’s successor John II of Jerusalem (d. 417 CE). Baumstark compares the handwriting to one of the palaeographical plates (no. 55) in Eugène Tisserant’s Specimina Codicum Orientalium (figure 4), highlighting, though, that it is “considerably younger”. However, Baumstark’s palaeographical judgement should not be readily trusted here. Two fragments of one and the same parchment codex were offered separately in Katalog 500 as nos. 15 and 16, which Baumstark dated two centuries apart, namely to the 10th and the 12th centuries CE. Tisserant dates MS Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Borg. Ar. 95, on which the facsimile in his Specimina is based to the 9th century CE.21 Given that olim Hiersemann 500/25 is written on paper, which started to be used more widely for Christian Arabic manuscripts in the 10th century CE, it is not unlikely that Hiersemann 500/25 was a 10th-century CE manuscript as well.

18. This is yet another feature it would have shared with Sin. Ar. 309. It leads us to the discussion of one more important piece of evidence in the search for the traces of this lost manuscript from al-Muqtaṭaf. Notably, Sinai’s Arabic manuscripts were catalogued by Margaret Dunlop Gibson (1843–1920) shortly after Grote had access to the monastery’s library. Her catalogue appeared in 1894, the same year the article was published in al-Muqtaṭaf. The cataloguing itself turned out to be somewhat frustrating, since more than 50 manuscripts were untraceable at the time; this could be ascertained based on an earlier numbering system. Some of these later resurfaced, others did not. One lacuna appears right after Sin. Ar. 309. The shelfmark MS Sinai, St Catherine’s Monastery, Ar. 310 (Sin. Ar. 310) now exists, but only because the number 310 was reassigned in 1950 during the Library of Congress expedition.22 In the old numbering system, manuscripts with the same content were grouped and assigned consecutive numbers, it is reasonable to assume that Hiersemann 500/25 used to be the former Sin. Ar. 310.

19. To sum up, the search for the traces of what appeared at first to be a lost manuscript of the Arabic Pauline Epistles from St Catherine’s Monastery led to one of the oldest copies of an Arabic translation of Cyril of Jerusalem’s Catechetical Homilies stored in the same monastery for at least eight centuries. Only at the end of the 19th century did a German collector dislocate it, and in doing so ultimately seems to have caused its destruction. Many more manuscripts from the Grote collection were destroyed during WWII, not only due to the fire at the University Library in Leuven. In this respect, his collecting activity has done irreparable damage to the cultural heritage of St Catherine’s Monastery. All that can be done now is to document these losses as accurately as possible.

Acknowledgements: I would like to express my thanks to Dawn Childress, Miriam L. Hjälm, Bert Jacobs, Grigory Kessel, Dorian Leveque, Alexander Treiger, and Vevian Zaki for their help in obtaining important information and material I needed for the research presented here. I am also grateful to Tim Curnow for copy-editing this text.

Peter Tarras is currently a research assistant in the ERC project MAJLIS (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich). Previously, Peter has worked for the Arabic and Latin Glossary (Julius-Maximilians-Universität, Würzburg). His areas of interest include the Bible in Arabic, intellectual history in the Near and Middle East, book history, manuscript studies, and provenance research. Peter is also interested in the communication of research to a broader audience and has recently launched his own blog Membra Dispersa Sinaitica, which is dedicated to the the dispersed manuscript heritage of St Catherine’s Monastery.

References