1. Sulochana – the one with beautiful eyes – was Indian cinema’s first female superstar. She rose to prominence in the 1920s, acting in a variety of roles: from telephone operator to popular sex symbol, Wild Cat of Bombay, becoming the industry’s most famous face. Born as Ruby Myers in a Baghdadi Jewish family in 1907 in the western Indian city of Pune, Sulochana was the first woman to act in the nascent Indian silent film era. When the industry shifted over the next three decades to Talkies and then to Technicolour, she too moved with it and established herself firmly, gaining popular titles such as swapno ki rani (dream girl/queen), romance ki rani (romance queen), as well as India’s quintessential ‘Modern Girl’.1

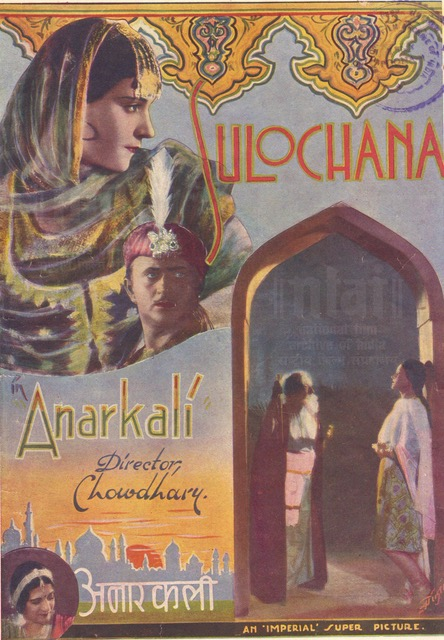

2. The legend goes, Sulochana at one point was paid more than the Viceroy – the British governor of India. After she moved to Imperial Film Company – the leading Indian production house of the time, her name became synonymous to it. She earned fame and fortune starring in the first silent film adaptation of the popular legend of ‘Anarkali’, released in 1928 based on the love story of the Mughal prince Salim, son of Emperor Akbar, and his beloved, the eponymous heroine, a courtesan and a commoner.

3. At the peak of her success in the 1930s, she launched her own production company, Rubi Pics, to take more control of her career with the arrival of the talkies, when Myers fell out of favour. A descendant of Arabic-speaking economic migrants to British India, Myers’ mother tongue was long replaced with English with the rapid success and therefore Anglicisation of the Baghdadi community. But she rose to the challenge, took a year off, learnt Hindi, and returned to the industry in 1932, releasing a talkie version of her blockbuster, Anarkali, in 1935, starring in the lead character.

4. Sulochana blazed the trail. With her and after her, an increasingly number of Jewish women arrived in Bollywood’s film studios, as they became ever more versatile in choosing roles, encompassing Mughal princesses to society vamps to proud, determined modern Indian women.

5. Another popular actress was Miss Rose, or Rama Katroum Rose Musleah, who was born in Calcutta in 1911 and moved to Bombay. She too soon became a big household name, and grew with the industry as it came to be known Bollywood. Then there were Pramila, Nadira, Ramola and many more – who joined the Cineworld, fought social prejudice against women as actors, and like Sulochana, overcame language barriers.

6. Calcutta-born Baghdadi Jewish scholar and documenter, Jael Silliman writes, ‘few members of Calcutta’s Jewish community were interested in Indian cinema, despite the booming film industry’. How did then the Jewish actresses find themselves in pioneering roles in early twentieth century indigenous film industry as it took root with ‘Bombay and Calcutta as its chief centres’?2

7. Silliman writes that ‘these film stars, Indianized for the screen, were considered beyond the pale of the Jewish community. They were included in the community as long as they kept their film world distinctly apart.’ This was exactly what these Jewish performing artists, who dwelt in the ‘in-between place’ in India3, did. They are remembered as the first female actors in Indian cinema.

8. They were Middle Eastern Jewish women playing taboo breaking ‘Indian’ characters: from chain-smoking vamps to femme fatales, as well as producers, releasing blockbuster films through their own successful production houses. They navigated between multiple identities in India, maintaining their Judeo-Arabic heritage while engaging with mainstream culture, emerging as some of the most recognisable icons of the silver screen.

9. How did they, in particular when many of them were not fluent in the native tongue, end up playing foundational female roles in the genesis of the Indian cinema? During the formative years of the industry, Hindu and Muslim women did not come forward to become professional artists, as acting was seen as a disreputable profession for women.4 Ruby Myers in fact turned down when she was first approached by a producer when she was working as an actual telephone operator. The producer then offered her a lead role as herself, and she appeared in Veer Bala, in 1925, under the stage name, Sulochana. The Jewish actors took on Sanskrit or Urdu names, to pass as Indians.

10. This marked a huge transformation in their collective identity as Jews of the Arab world ‘who lived in India but were never of India’, as their community until now ‘remained aloof from Indianness’, spoke English, ‘with no intermediary of Hindustani, which they used only for trade and to speak to servants’.5

11. As an increasingly number of Jewish women arrived at the door of Bollywood’s film studios, they became ever more versatile in choosing roles, encompassing Mughal princesses to society vamps. As this trend continued, one Kolkata born actress, Esther Victoria Abraham who took an archetypal Bengali name, Pramila, appeared in a number of both Bengali and Hindi language films. She went on to become the winner of the first ever Miss India beauty pageant in 1947, as India was achieving Independence after 200 years of British rule.6

12. It was British colonialism that initially drove Baghdadi Jews to move eastwards from Iraq and the wider Mediterranean basin. In 1798, Rabbi Shalom Obadiah Ha Cohen arrived in Calcutta, ‘the first Arabic-speaking Jew to settle’ in the city, ‘which, at the turn of the eighteenth century, was a centre for trade and the commercial heart of British India.’7 Known as the founder of the community in Calcutta, Rabbi Ha Cohen came from Aleppo, northern Syria, not Iraq. The Baghdadis who settled in Asian Jewish diasporas, comprised of travelling Jews from the Middle East. In India and several Far Eastern satellite spots the community collectively came to be known as ‘Baghdadi’, the moniker the British gave them. Their settlement from the mid eighteenth century in India coincided with the rise of port cities and economic mobility under imperial expansion.

13. Impacted by colonial influences, the Baghdadi community established itself as ‘a commercially successful class’ in these booming port cities.8 Film historian, Sumita Chakravarti says that the arrival of motion picture in the early twentieth century ‘attracted a large number of business people, artists and craftspeople into film production.’9

14. The Middle Eastern Jews soon became centrally involved in Indo-Asian commerce and later in the entertainment industry, in ways disproportionate to their ‘micro-minority’ status, largely because of the opportunities afforded by the British Raj, notwithstanding that these historically ‘mobile traders’, picked up new professions with the change of times.10 As they began their new lives in Calcutta (Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), Poona (Pune), the Baghdadi Jews demonstrated meteoric rise in their social status.

15. What is interesting is that even after almost a hundred years of their settlement in Indian cities, they aspired to become more English than Indian. In her scholarly work, “Jewish Portraits Indian Frames”, Jael Silliman, the tireless curator of Baghdadi Jewish memory culture, writes that her ancestors ‘occupied an ambivalent position…in the colonial structure’, and had a complicated relationship with India. ‘They were neither Indian, nor Western, brown nor white, but sandwiched between the two, at once insiders and outsiders….They clamoured unsuccessfully for European status, which the British never gave them.’11

16. Amid this fog of identity crisis, a handful of Baghdadi Jewish actresses found themselves facing a dilemma. although their silent era performances established them as Indian film stars with their stage names, the problem emerged when the industry moved to talkies. While in silent era productions they could successfully pass as Indian without adequate Hindi, in talkies, even the most successful actors struggled to find roles beyond vamps and distorted, fantasised versions of Europeans – the so called ‘loose women’, or sidekicks to lead characters.

17. In the last quarter of their Indian diaspora, the Baghdadi Jews arrived at the juncture of their community’s redefinition. Its social fabric crumbled in the twilight years of Empire, ushering in a resurgence of a hybrid Indian-Jewish identity among the descendants. Israeli sociologist of Baghdadi Jewish origin, Yehuda Shenhav, suggests that in a world where colonial, post-colonial and neo-colonial spaces co-exist, ‘groups that have been left out of or pushed out of the central narrative take the stage’12.

18. The Jewish actresses literally took the ‘stage’. In that fertile environment, manoeuvring between gender, Judaism and modernity, they reshaped Jewish identity through the alternative narratives of Bollywood’s silver screen.

References

- https://www.bombayjewisharchives.com/blank-11-1. ↩︎

- Silliman, Jewish Portraits, p. 66. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 145. ↩︎

- Mukherjee, “Jewish Actresses”. ↩︎

- Katz, Studies of Jewish Indian Identity, p4), quoting ‘On India’s Baghdadi Jews’, Timberg, Jews in India; Ezra, Turning Back; and Musleah, On the Banks. ↩︎

- Jewish Women’s Archive: Sharing Stories, Inspiring Change, URL: https://jwa.org/thisweek/dec/30/1916/birth-bollywood-actress-pramila. ↩︎

- Silliman, Jewish Portraits, pp. 128–129. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 66. ↩︎

- Chakravarti, National Identity, pp. 33–34. ↩︎

- Silliman, Jewish Portraints, p. 168. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 18. ↩︎

- Shenhav, The Arab Jews, p. 53. ↩︎

Literature

Chakravarti, Sumita S. National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema 1947–1987 (Austin: University of Texas, 1993).

Elias, Flower. The Jews of Calcutta: The Autobiography of a Community, 1798–1972 (Calcutta: The Jewish Association of Calcutta, 1974).

Ezra, Esmond David. Turning Back the Pages: A Chronicle of Calcutta Jewry. 2 vols. (London: Brookside Press, 1986).

Geller, Jay. The Other Jewish Question: Identifying the Jew and Making Sense of Modernity (New York: Fordham Univ. Press, 2011).

Guttman, Anna Michal. “Our Brother’s Blood: Interreligious Solidarity and Commensality in Indian Jewish Literature.” Prooftexts: A Journal of Jewish Literary History, 40, no. 2 (2022): pp. 71+. Gale Academic OneFile, dx.doi.org/10.2979/prooftexts.40.2.03. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Hyman, Mavis. Jews of the Raj (London: Hyman Publishers, 1995).

Isaac, I. A. A Short History of Calcutta Jews (Calcutta: Telegraph Association Press, 1917).

Jewish Women’s Archive: Sharing Stories, Inspiring Change. URL: https://jwa.org/thisweek/dec/30/1916/birth-bollywood-actress-pramila.

Katz, Nathan. Studies of Jewish Indian Identity (New Delhi, Manohar pub., 1995).

Mukherjee, Manjari. “Jewish Actresses in Bollywood”. Jewish Women’s Archive, March 3, 2025, URL: https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/jewish-actresses-bollywood.

Musleah, Rabbi Ezekiel Musleah N. On the Banks of the Ganga: The Sojourn of Jews in Calcutta (North Quincy, MA, Christopher Publishing House, 1975).

Nandy, Ashis. The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983).

Richards, John F. “Opium and the British Indian Empire: The Royal Commission of 1895.” Modern Asian Studies, 36, no. 2, (2002): pp. 375–420. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3876660. Accessed 9 May 2025.

Roland, Joan G. Jews in British India: Identity in a Colonial Era (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1989).

Shenhav, A Yehuda. The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006).

Silliman, Jael. Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames: Women’s Narratives from a Diaspora of Hope (London, New York, Culcutta: Seagull Books, 2001).

—————– “Crossing Borders, Maintaining Boundaries.” Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, 1, no. 1 (1998): pp. 57–79.

—————–The Man With Many Hats (Calcutta: self published, 2013).

Timberg, Thomas, A. ed. Jews in India. (Vikas Publishing House, 1986).

—————— “Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Jews.” In Nathan Katz (ed.), Studies of Indian Jewish Identity (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 1995).

Yehuda, Zvi. The New Babylonian Diaspora: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Community in Iraq, 16th-20th Centuries C.E. Brill (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2017).

Lipika Pelham is a historian specialising in early modern Sephardi Jewish revival in post-Reformation Amsterdam. Her current research examines the history of the settlement of Jews from Ottoman Mesopotamia in Indian cities from the 1790s to World War II, focusing on the ‘Baghdadi’ satellite community’s quest for a Jewish-European-Indian identity. Pelham’s work explores the many ways Jewishness is articulated and contested across geographies in the post-colonial world, with a particular emphasis on the resurgence of a Non-European Jewish Internationalism. This post was written during her VW-Fellowship at the Research Centre of Jewish-Arabic Cultures.

Suggested Citation: Lipika Pelham, “The Vamp of Baghdad: How Jewish actresses shaped early 20th century Indian cinema”, Munich Research Centre for Jewish-Arabic Cultures Blog, 7 November 2025, URL: https://www.jewisharabiccultures.fak12.uni-muenchen.de/the-vamp-of-baghdad-how-jewish-actresses-shaped-early-20th-century-indian-cinema/. License: CC BY-NC 4.0.