1. As Arabic slowly emerged as the lingua franca for Eastern Syrian learning and study, new copies of biblical texts were compiled for an increasingly Arabic-speaking audience. As part of this, the Syro-Hexapla – studied by experts in scripture from late antiquity on, because of its textual adherence to the versions of the Bible found in the Septuagint – was translated several times from Syriac into Arabic. One early translation of the Syro-Hexaplaric Pentateuch into Arabic is ascribed to al-Ḥārith ibn Sinān ibn Sunbaṭ al-Ḥarrānī.1 It is known that the historian al-Masʿūdī, who died in 956 CE, refers to this translator; that year, then, marks the terminus ante quem, before which he must have been active.2 With respect to biblical literature, aside from the Pentateuch, al-Ḥārith also seems to have translated books of wisdom and compared poetic elements of scripture in Greek Orthodox and Arab Christianity and Judaism.3 However, it remains unclear, which doctrine he adhered to: Nasrallah makes arguments for him being a Melkite (and so adhering to the doctrine that Christ has two natures), Vollandt sees him among Miaphysite scholars.4

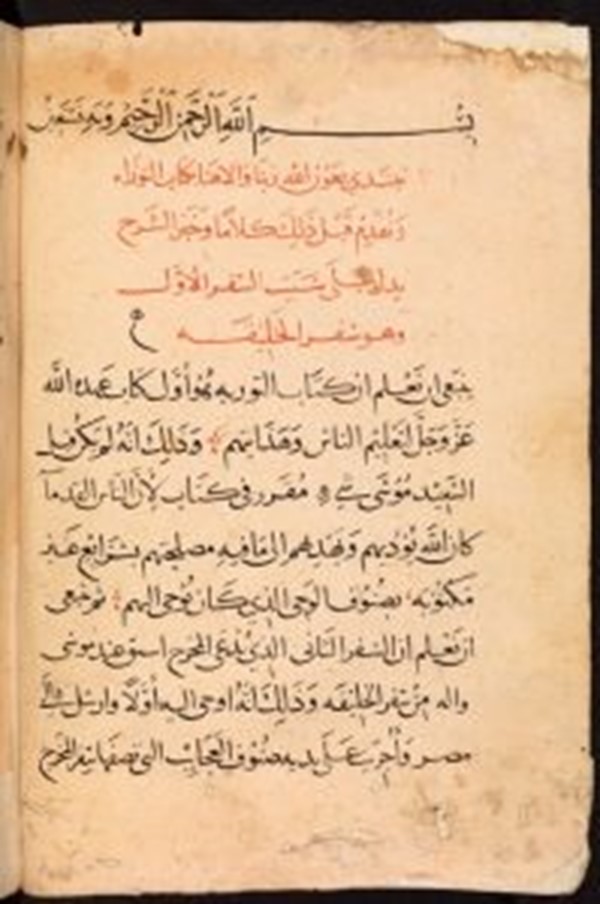

2. Some copies of the Pentateuch translation by al-Ḥārith include an introductory tractate, entitled al-Risāla, which primarily answers philological questions about the transmission of Origen’s Hexapla. Important for the present contribution are short forewords and indices in Arabic for each book of the Pentateuch. In contrast to those corresponding to the other four books, the foreword to Genesis is longer and, recounting the tradition of hexaemeral literature, deals with questions related to the moment of creation. One manuscript, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud. Or. 258 (olim A 147), referred to in the following as “OX”, may be identified, according to Vollandt, as a late Melkite copy written not before the thirteenth century CE. That manuscript names al-Ḥārith as the translator of “the first book of the Torah according to the Seventy-Two“ (التورية على ما نقله اإلثنان والسبعون) (fol. 115v). The foreword (الكلام الوجيز المقدم) (fol. 10v–18v) immediately precedes an index (fol. 19v–30r) and the main text of Genesis (fol. 30v–115v). Similar palaeographical features indicate that all these parts were written by the same hand.

3. Here, I would like to examine one potential source that the author of the foreword on Genesis may have relied on and suggest that its style and content can be read in the context of East-Syriac doctrine. The widely influential works of Theodore of Mopsuestia, as well as those of later Syriac exegetes like Ishodad of Merv and Thedore bar Konai circulated within the community that followed this doctrine. So, is it possible to establish through comparative analysis correspondences between the Arabic foreword and the works of these authors? Fortunately, there is a potential Vorlage of the foreword: it closely resembles a short piece of a Syriac commentary that van Rompay, for various reasons, relates to the East-Syriac doctrine.[5]

4. The work in question is known to belong to an anonymous commentary on the Pentateuch. This commentary covers the Old and New Testaments and is preserved in different lengths and recensions in nine manuscripts. Of these, van Rompay edited MS (olim) Diyarbakır 22, hereafter “D”, in CSCO 483 and accompanied it with a French translation in CSCO 484.[6] The text of the commentary in this manuscript is special in that it presents scholions on Genesis 1:1 to Exodus 9:32, which vary from the text of the other witnesses (such as that in MS Vatican, BAV, Sir. 578). Van Rompay estimated the date of this recension to the end of the eight or the first half of the ninth century, the time when Ishodad of Merv and Theodore bar Konai were active. A description of the progression of eras in the Syriac text, ending with the reign of the caliph al-Mahdī (d. 785), may support this estimation on historiographical grounds.

5. The segment of the commentary on Genesis 1:1 to Exodus 9:32 that is of importance here is found on the recto and verso of fol. 2 in D and begins with an „Instruction [and] Introduction to Genesis“ (ܢܘܗܪܐ ܕܒܪܝܬܐ ܥܠܬܐ).[7] The introduction focuses on soteriology, and quotes 1 Corinthians 9:9-10, Psalms 104:14, and Job 38:7. In the last paragraph it has the closing formula: “Now, we are content with the little that has been said until here” (ܗܠܝܢ ܗܟܝܠ ܩܠܝܠ ܥܕܡܐ ܠܣܪܟܐ ܣܦܩ̈ܢ). The text then continues with a scholion on Genesis 1:1, beginning with an interpretation of the word ܐܘܪܝܬܐ, the Syriac designation for the Pentateuch. It then offers a linguistic analysis of the meaning of “in the beginning”. It quotes Proverbs 1:7, John 1:1, and John 15:27 to support an intertextual reading of Genesis 1:1 that rejects any measurable duration of the beginning (ܒܪܫܝܬ), in contrast to the first starting point of the creation (ܡܫܘܚܬܐ ܕܛܘܪܐ ܡܕܝܡ). The scholion concludes with identifying the seven substances that were created on the first day (and night): heaven, earth, fire, water, air, immaterial beings, and darkness.

6. The foreword in OX bears close stylistic resemblance to the anonymous commentary in D. It must be noted, however, that the first third of the Arabic foreword about rational beings (الناطقون) in creation can only be hypothesised to correspond to the Syriac text, as in D this starts in the middle of a discussion on that same theme – the beginning of the text is not preserved in D, and consequently the following observations on stylistic parallels cannot cover the first paragraphs of the Arabic foreword.[8] The first if these parallels is that both the Arabic text and the Syriac commentary name the above mentioned reign of al-Mahdī (ܡܚܡܛ ܐܠܡܣܝ > محمد المسيح).[9] Second, both texts partly resemble the form of quaestiones and the scholion is given in the form of a running commentary, beginning with the quotation of Genesis 1:1, discussing phrasing and lexicality. Third, all quotations exhibited in the relevant Syriac segments are also used in full in the Arabic text with the same rationale.[10] Fourth, neither text mentions any (patristic) authors or commentators by name, but both recall the authority of Moses in passages of interpretation; such paragraphs have the phrasing “Moses reports”, “Moses informs”, or “Moses determined”. Fifth, the Arabic text imitates important theological concepts from the presumed Syriac Vorlage oftentimes word by word: for example, the concept of moral mutability (ܡܨܛܠܝܢܘܬܐ > مثل), the immutability of God (ܠܐ ܡܬܕܪܟ > لم يدرك جوهره), the moment of creation in silence (ܠܐ ܣ̣ܡ ܡܠܬܐ > لم […] يحتج إلى صوت مسموع), or the simultaneous creation of the seven substances in silence (ܫܒܥܐ ܟܙܢ̈ܐ ܒܫܬܩܐ > السبعة الجواهر معًا كما اخبرنا انقَا بالصمت لا بالصوت).

7. However, it appears that at the end of the Arabic text the compiler deliberately added information concerning Christ’s eulogy, not present in the Syriac text. If we ascribe this foreword to al-Ḥārith – along with the Risāla and the Arabic translation of the Syro-Hexapla – then this addition suggests that he may have manipulated the text to mark a preferred denominational stance:

| وهو التجديد الذي يكمل على يدي يشوع المسيح الذي جا من السما وتايس من روح القدس ومن مريم العذرى المهرة وولد منها الاهًا أزليًا وانسانًا[11] | ܗܘ̇ ܕܒܡܕܢ ܡܫܝܚܐ ܡܬܓܡܪ ܡܐ ܕܐܬܐ ܡܢ ܫܡܝܐ [12] |

| […] and this is the completion, which is complete with Jesus Christ, who comes down from heaven and becomes man through the Holy Spirit and the immaculate Virgin Mary. From her was born one eternal God and transient man. | […] what will be completed in Christ when he comes down from heaven. |

8. The expanded eulogy refers to the Virgin Mary as the theotokos and underlines the hypostatic union of Chist, therefore indicating West-Syriac influence. Although the Arabic foreword was corrupted throug the process of transmission to a certain degree, and so may exhibit individual readings only found in OX, three other manuscripts attest to the exact same addition.[13]

9. In summary, then, the Arabic exegetical foreword presented here demonstrates a clear imitation of the style and content of the anonymous Syriac commentary found in D, and is united with the literal rendering of the Syro-Hexapla in OX to inform a reader of Arabic. Whether this patron – referred to in the Risāla – requested the text from al-Ḥārith for academic purposes is difficult to answer. It would seem that he was especially interested in the Syro-Hexaplaric recension and in the theories outlined above concerning the creation myth known from Eastern Syriac commentaries. In fact, the degree of imitation in this text of the commentary found in D, suggests something that is beyond the scope of this contribution: namely that the Syriac commentary served as the Vorlage for the Arabic text, and that al-Ḥārith produced a translation of it. Additional questions, as yet unanswered, relate to al-Ḥārith’s own exegetical contributions in this work, and also deal with intertextual phenomena found in his Arabic translation of the Syro-Hexaplaric Pentateuch.

Sebastian Hieke completed his MA in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in 2023. As a result of his time as student assistant in the DFG-funded project Independence and Diversity: Unknown Qaraite Bible Commentaries in Judeo-Arabic from the Early Classical Age, he has developed a strong interest in the transmission history of pre-modern biblical literature in Arabic and its varieties. His MA thesis, on which the present article is based, deals with the influence of Syriac exegetical commentaries on the works of al-Ḥārith ibn Sinān. It also examines the use of chapter headings and the indexing of Syro-Hexaplaric kephalaia in the book of Genesis, which al-Ḥārith applied in his Arabic translation of the Pentateuch.

Suggested Citation: Sebastian Hieke, “Traces of an Anonymous Syriac Commentary in al-Ḥārith ibn Sinān’s Deliberations on Genesis 1:1”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 20 March 2024, URL: https://www.jewisharabiccultures.fak12.uni-muenchen.de/biblia-arabica-blog-traces-of-an-anonymous-syriac-commentary-in-al-%e1%b8%a5arith-ibn-sinans-deliberations-on-genesis-11/. License: CC BY-NC.