Scholarly interest in the Bible in Arabic has surged in recent decades. While traditionally specialists in the textual history of the Bible downplayed the importance of Arabic Bible manuscripts, scholars have increasingly shown the potential significance of these manuscripts, not only for the textual history of the Bible in general, but especially for our understanding of the communal lives of Arabicized Christians and Jews, as well as their theologies. Of the Christian scriptures, the study of the Arabic Gospel manuscript tradition has been especially active, represented in the publication of Hikmat Kashouh’s 700-page monograph, in which the author produces manuscript families based on detailed verbal analysis of over 200 manuscripts. ((Hikmat Kashouh, The Arabic Versions of the Gospels: The Manuscripts and their Families. Berlin: De Gruter, 2012.))

2. One aspect of these manuscripts which has not been given appropriate attention is the linguistic study of the Gospel manuscripts. By far the most thoroughly-studied Gospel manuscripts are Kashouh’s Families A and H. ((Family A includes the 9th – 10th century MSS Vatican Borg. Arabic MS. 95, Sinai Arabic MS 74, Sinai Arabic MS 72, Sinai Arabic MS 54, Sinai Arabic MS 71, among a few others. Family H consists of Vatican Arabic MS. 13. On Vatican Arabic MS. 13, see Kashouh, Arabic Versions of the Gospels, pp. 147-152; Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, “An Early Fragmentary Christian Palestinian Rendition of the Gospels into Arabic from Mār Sābā (MS Vat. Ar. 13, 9th c.),” in Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 1 (2013): 69-113. For Family A, only Sinai Arabic MS. 72 has attracted focused linguistic comment. See Samir Arbache, “Une version arabe des Évangiles: Langue, texte et lexique,” PhD diss., Université Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux III, 1994; idem, L’Évangile arabe selon saint Luc: texte du VIIIe siècle, copié en 897, édition et traduction = al-Inǧīl al-ʿArabī bišārat al-qiddīs Lūqā. Brussels: Éditions Safran, 2012.)) However, these studies, still few in number, rely on the historical linguistic framework of a single work, namely Joshua Blau’s three-volume grammar of what he calls “Ancient South Palestinian.” ((Joshua Blau, A Grammar of Christian Arabic. Based Mainly on South-Palestinian Texts from the First Millennium. 3 Volumes. Louvain: Peeters, 1966/7. )) Indeed, I have been unable to identify a single work produced on any Arabic Bible manuscript or tradition since Blau’s grammar appeared that does not cite, and basically reproduce, both Blau’s interpretation of the linguistic phenomena as well as his methodology. Since I disagree with both, it is worth briefly exploring Blau’s still-dominant framework. I will then argue for a different approach, and provide a few brief case studies.

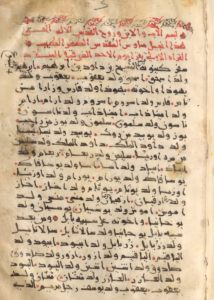

f. 3r (897 CE). Photograph courtesy of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt.

3. Blau’s grammar is based on (mostly unvocalized) manuscripts produced in the monasteries of southern Palestine before 1000 CE. He considered Christian Arabic texts, insofar as they differ from Classical Arabic in numerous ways, some of the earliest examples of “Middle Arabic.” Formally, Blau considered “Middle Arabic” as a historical phase of the language, between “Old Arabic” (= Classical Arabic) and “Neo-Arabic.” However, Blau also considered “Neo-Arabic,” structurally identical to the modern dialects, to have arisen quickly and dramatically as a result of imperfect acquisition of Arabic by the conquered peoples. In fact, Blau believed that the linguistic changes that differentiated “Neo-Arabic” from “Old Arabic” were mostly complete by the time of the first “Middle Arabic” compositions. So in practice Blau rarely, if ever, identified a feature as historically “middle” (i.e., representing a living feature between Old and Neo-Arabic). Instead, he placed most features into one of three categories: (1) Classical Arabic, (2) Neo-Arabic (non-Classical features also attested in a modern dialect), or (3) Grammatical mistakes. As a consequence, and despite the title, Blau’s “grammar” is less a documentation and description of the features and their distributions within and across the manuscripts, and more a catalog of non-Classical features, each of which is explained either by appeal to a modern equivalent, or by postulating the source of the scribe’s error.

4. Over the past decade or so, both new discoveries and novel methodological considerations have combined to problematize this paradigm to the point that it should be abandoned. First, contrary to Blau’s assumptions, “Old Arabic,” by which he meant the Arabic of the pre-Islamic period, was neither homogeneous nor identical to Classical Arabic. Ahmad Al-Jallad’s work on, e.g., the Safaitic, Hismaic, and Nabataean Arabic corpora of inscriptions has documented a great deal of pre-Islamic Arabic diversity. These inscriptions, which span from southern Syria, Palestine, and the Sinai to western and central Arabia, and conventionally date beginning in the 4th century BCE (and likely earlier), attest varieties in which many changes that characterize the modern dialects, such as the breakdown of case and mood, had begun but were not complete. Using traditional terminology, then, these pre-Islamic varieties of Arabic were in that sense “Middle Arabic.” But they were also linguistically more archaic than what the grammarians described. ((For example, Hismaic lacked a definite article (which proto-Arabic likely lacked), and Safaitic spellings suggest that in those dialects sequences of aya and awa had not yet contracted. So, for example, Safaitic attests B-Y-T بَيِتَ “he spent the night” where Classical Arabic has باتَ bāta, and ʾ-T-W أَتَوَ “he came” where Classical Arabic has أَتَى ʾatā. The pre-Islamic dialects thus could not have descended from Classical Arabic, in which the shift from aya and awa to ā had already taken place. “Old Arabic” therefore looked considerably different than what Blau thought, while “Middle Arabic” features are simultaneously attested well before the Islamic period.))

5. These discoveries led Marijn van Putten and me to re-consider the linguistic nature of the Quranic consonantal text by focusing on the evidence for nominal case therein while approaching the text without the imposition of subsequent Classical norms. Based on a close study of the orthography, as well as internal evidence based on rhyme, we argued that the earliest layer of the Quran attested a partial case system, identical neither to Classical Arabic nor the modern dialects. It is, in other words, also “Middle Arabic,” at least from the standpoint of nominal case inflection. ((Marijn van Putten and Phillip W. Stokes, “Case in the Qurʔanic Consonantal Text,” in WZKM 108 (2018): 143-179.))

6. In his recent monograph, Van Putten poses the question of what the language of the Quran is, and demonstrates that “Classical Arabic” cannot meaningfully be the answer. ((Marijn van Putten, Quranic Arabic: From its Hijazi Origins to its Classical Reading Traditions. Leiden: Brill, 2022)) By drawing on data from the earliest grammarians, he shows that what we think of as Classical Arabic was originally a diverse collection of features with no real preference given for one over the other. The process wherein only the features we associate with Classical Arabic were standardized took several centuries (Van Putten suggests the 9th/10th centuries CE based on manuscript evidence). Even then, it is not at all certain that this emergent Classical Arabic register would become the primary, let alone sole, target of authors in Christian and Jewish communities.

7. The implications of this revolution in the study of the history of Arabic have already been brought to bear on the study of a famous early Christian Arabic composition. In 2020, Ahmad Al-Jallad published a detailed study of the Damascus Psalm Fragment, a text discovered by Bruno Violet in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus which contains an Arabic translation of Psalm 77 (MT 78) transliterated in Greek letters. ((Ahmad Al-Jallad, The Damascus Psalm Fragment: Middle Arabic and the Legacy of Old Higāzī. Chicago: Oriental Institute, 2020.)) Al-Jallad connects the language with the Hijaz (which he calls “Old Higazi”), and argues that it represents a colloquialized development of this Old Hijazi (identical to the language of the Quranic Consonantal Text), which he proposes was an early prestige language in the Levant under the Umayyads. He concludes with the observation that, for manuscripts and papyri produced in the first few Islamic centuries at least, assuming a Classical Arabic target is unwarranted due to the absence of a coherent and prescriptive Classical Arabic register.

8. The “Ancient South Palestinian” manuscripts Blau studied, including several of the oldest known Arabic Gospel manuscripts, come from the same milieu as the Damascus Psalm Fragment. I contend that the proper way to study these manuscripts is by documenting each feature, with variation in its distribution quantified, and pragmatic contexts documented as fully as possible. Calling something “Middle Arabic” is mostly telling us what it is not (i.e., Classical Arabic), whereas for a proper understanding of the linguistic situation we must define what it is. Finally, It remains to be demonstrated whether, where and when we have positive evidence for interactions with what we call Classical Arabic in the Arabic Gospel manuscripts (and Christian corpora in general), and what dynamics animated those interactions.

9. Before turning to the case studies, I wish to address a recurrent claim regarding the possibility and usefulness of linguistic study of the Arabic Bible manuscripts. It is often suggested that their status as translations makes them less useful for linguistic analysis than original compositions. ((Cf. Ronny Vollandt, “The Status Quaestionis of Research on the Arabic Bible,” in Nadia Vidro et al (eds.), Studies in Semitic Linguistics and Manuscripts: A Liber Discipulorum in Honour of Professor Geoffrey Khan, pp. 442-467. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press, 2018; Blau, Grammar of Christian Arabic, p. 54.)) On the one hand, it is very probable that certain linguistic domains, especially word order and the lexicon, are affected to varying degrees by a scribe’s desire to imitate the source text, etc. On the other hand, the degree to which these translations would be grammatically unusual to someone other than their authors, or the monastic community, is far from clear. Any genre, whether written or spoken, will inevitably affect the grammar of the text. Studies of the syntax of modern spoken Arabic reveal a great deal of possible syntactic constructions, depending on the pragmatics of the context. ((See especially: Kristen Brustad, The Syntax of Spoken Arabic: A Comparative Study of Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti Dialects. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown, 2000.)) It is likely that syntax governed by the formalized conventions of poetry and prose from which we tend to draw our examples of “good” Classical Arabic was, compared with other registers and genres, quite restricted in many original compositions. At the same time, just as modern Arabic speakers incorporate constructions and vocabulary from, e.g., Media Arabic, using them to varying degrees in their own extemporaneous speech depending on the topic and context, it seems also probable that, over time and as the language of the Bible in Arabic became a real part of the input of Arabic speaking Christians, so too these constructions and lexical items became a part of “normal” Arabic in Christian communities.”

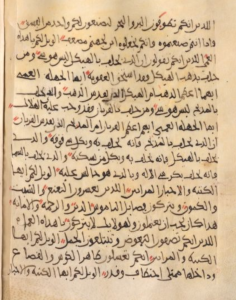

f. 1v (1289 CE). Photograph courtesy of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt.

10. In the remainder of this post I will present two test-cases. The first is verbal mood inflection in the manuscripts of Kashouh’s Families A, C, and D. The second feature is pronominal suffix harmonization patterns in vocalized manuscripts from the 11th century CE and following. My discussion of each is based on data I have gathered directly from the Arabic Gospel manuscripts and represents abbreviated discussions found in forthcoming publications.

11. One of the main features considered by Blau and others to be characteristic of the “Neo-Arabic” that emerged in the immediate aftermath of the Islamic conquests is the loss of verbal mood inflection (indicative, subjunctive, and jussive). Though only asserted, rather than demonstrated, the assumption has led scholars simply to list non-Classical instances of indicatives in non-indicative contexts, and vice versa, alleging they came about by mistake. If we simply take a few examples from each category, the picture appears quite chaotic, as in Blau’s presentation. Indicative forms occur in non-indicative contexts, and vice versa (all quotations from Sinai Arabic MS. 74):

Indicative Contexts:

خذ الصبي وامُه وانطلق الي ارض اسرايل لان الذين يطلبون نفس الصبي قد ماتوا

“Take the child and his mother to the land of Israel, because those who were seeking the life of the child have died” (Matthew 2:20, f. 3v)

عماه يبصروا وكسُح يمشوا وبرصُ يستنقوا

“The blind see, the lame walk, lepers are healed” (Matthew 11:4, f. 22r)

Non-Indicative Contexts:

ليس تستطيعوا تتعبدوا لله والمال

“You cannot serve God and money” (Matthew 6:24, f. 11v)

وكانوا يطلبون اليه ان يمسون هدب ثوبه فقط

“And they were seeking him in order to touch the hem of his cloak” (Matthew 14:36, f. 33r)

12. However, when we thoroughly document and quantify the “Middle Arabic” usages of indicative and non-indicative in the plural (i.e., ūn vs. ū forms) across manuscripts from Families A, C, and D, a different picture emerges. For example, the vast majority of indicative (ūn) forms occur in indicative contexts, and only rarely in non-indicative ones, whereas non-indicative forms frequently occur in both contexts:

| Sinai Arabic MS. 74 (A) | Vat. Borg. Ar. MS. 95 (A) | Sinai Arabic MS. 72 (A) | Sinai Arabic MS. 71 (A) | Sinai Arabic MS. 75 (C) | Sinai Arabic MS. 70 (D) | |

| Indicative in Indicative Contexts | 83% | 86% | 87% | 84% | 89% | 91% |

| Non-Indicative in Non-Indicative Contexts | 62% | 65% | 61% | 58% | 77% | 71% |

13. While this data is typically interpreted as interactions between a colloquial that had lost mood distinction trying to approximate a register that kept it, ((Blau, Grammar of Christian Arabic, p. 262 ff.)) I contend that the Gospel manuscript data provides a window into a change-in-progress from a system similar to Old Arabic towards one more familiar in modern dialects, yet which was not complete. It is thus actually an example of “Middle Arabic” in the historical sense. This interpretation is further suggested by the fact that the frequency with which non-indicatives occur in historically-indicative contexts is not even across indicative contexts. In other words, the non-indicative is not equally likely to occur in every indicative context. There is a clear pattern across the manuscripts. Syndetic relative clauses, for example, are consistently much likelier to trigger the use of the indicative than, e.g., main verbs. When verbs occur in interrogative or negated clauses, they are much likelier to be non-indicative. So, the order looks like this:

Verb of Syndetic Relative Clause > Main Verb > Negated Verb > Verb + Interrogative.

14. The system is one in which pragmatics, and especially speaker confidence and certainty, determine verbal mood more than syntax. The non-indicative has expanded most in contexts in which speaker certainty is low. This development is typologically common, and eventually resulted in the historical non-indicative (-ū) being generalized to all contexts, a change that stands behind the distribution of many (though not all!) modern dialects.

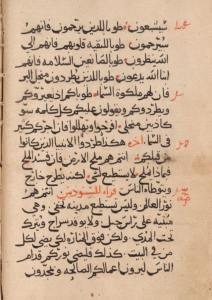

f. 5v (13th CE). Photograph courtesy of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt.

15. While the manuscripts included above have been the object of some linguistic commentary, very few later, vocalized Gospel manuscripts have been. I hope to show that such study can reveal a great deal via a quick examination of the harmonization patterns of the third person masculine pronominal suffixes as manifested in some vocalized Gospel manuscripts. Many attest non-textbook Classical Arabic patterns. Readers will likely be familiar with the standard Classical Arabic paradigm, wherein the unmarked realization of these pronouns is with a u vowel, except when preceded by –i / ay, which trigger assimilation to the high vowel:

| Base | Ci | Cī | Cay | |

| 3ms | kitāb-u-hū | kitāb-i-hī | fī-hi | ʿalay-hi |

| 3mp | kitāb-u-hum | kitāb-i-him | fī-him | ʿalay-him |

This textbook pattern is not, however, the only one mentioned – and sanctioned – by grammarians like Sibawayh and Al-Farrāʾ. In fact, they note the existence of dialects in which no harmonization takes place, attributing such forms to the dialects of the Hijaz: kitāb-i-hū, fī-hu, ʿalay-hu, etc.

16. While no study of the patterns in Christian manuscripts in general has been undertaken, multiple patterns exist. I have documented the following in Arabic Gospel manuscripts dating from the 13th to the 15th centuries CE, belonging to Kashouh’s Families J (each sub-family, Ja, Jb, and Jc) and F: ((The data and analysis here is taken from a forthcoming paper: Phillip W. Stokes, “bi-hī, bi-him…fī-hu? Pronominal suffix harmonization diversity in some vocalized Christian Arabic Gospel manuscripts,” in Journal of the American Oriental Society.))

| MS. | bi + 3ms | Ci + 3ms | Cay + 3ms | Ci + 3mp |

| Sinai Arabic MS. 89 (Jb) | bi-hu | kitābi-hu | ʿalay-hu | kitābi-hum |

| Sinai Arabic MS. 91 (Jb) | bi-hi | kitābi-hu | — | kitābi-hum |

| Sinai Arabic MS. 76 (Jc) | bi-hi | kitābi-hu, kitābi-hi | — | kitābi-hum |

| Sinai Arabic MS. 115 (Ja) | bi-hi, bi-hu | kitābi-hu, kitābi-hi | ʿalay-hi, ʿalay-hu | kitābi-him, kitābi-hum |

| Sinai Arabic MS. 146 (Ja) | bi-hi | kitābi-hi | ʿalay-hi | kitābi-him |

| Leiden Or. MS. 561 (F) | bi-hu | kitābi-hi, kitābi-hu | ʿalay-hi | kitābi-humā (du.) |

Some (such as Sinai Arabic MS. 89) look like Hijazi Arabic, whereas others attest an interesting hybrid, wherein the suffix harmonizes (hu > hi) only when suffixed to the preposition bi; otherwise, the vowel is ubiquitously u even when following i / ay. While this might appear idiosyncratic, and it is not mentioned by the grammarians, it is actually a well-attested pattern in vocalized Quranic manuscripts! ((Marijn van Putten and Hythem Sidky, “Pronominal Variation in Arabic among the Grammarians, Quranic Reading Traditions and Manuscripts,” in R. Villano (ed.), Formal Models in the History of Arabic Grammatical and Linguistic Tradition, special issue of Language & History 65:1 (forthcoming).)) And since the fully-vocalized Quran is one of the prime examples of Classical Arabic, this can hardly be considered a non-Classical feature! Sinai Arabic MS. 146 is the only manuscript of the group that attests the textbook Classical pattern. As the parallels in earlier corpora attest, these patterns reflect variation that is old but which continues, at least among Christians and Jews, ((For a similar pattern in Judaeo-Arabic, see: Phillip W. Stokes, “In the Middle of What? A Fresh Analysis of the Language Attested in Judaeo-Arabic Commentary on Pirqê ʾĀvōṯ (The Sayings of the Fathers), Middle Arabic, and Implications for the Study of Arabic Linguistic History,” in JSS 66.2 (2021): 379-411.)) long after the “textbook” pattern became dominant elsewhere.

17. The linguistic study of the Arabic Gospels, and indeed the Arabic Bible, is in many ways still in its infancy. I do not mean to downplay the significance of works already undertaken; however, I hope to have made a strong case that a different approach to these manuscripts is both warranted and potentially fruitful. The goal should first and foremost be to understand the distribution of the features attested in each manuscript, compare it with other manuscripts, and contextualize it all within the larger picture of Arabic linguistic history. Such diachronic work is, in turn, crucial for sensitive diachronic readings of the interactions between the registers with which Christian scribes interacted when creating each manuscript.

Phillip W. Stokes (PhD, University of Texas at Austin) is an assistant professor of Arabic in the Department of World Languages and Cultures at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He specializes in Arabic and Semitic linguistics, and his scholarship focuses on the linguistic history and development of Arabic. He regularly works on several corpora, from the pre-Islamic inscriptions in the Safaitic script, the Quran, various Middle Arabic corpora, to the modern Arabic dialects. His current work is on the language varieties and diversity attested in the corpus of Christian Arabic Gospel manuscripts.